Mapping Latino Odysseys

Students bring context to hotly contested debate

by MaryAlice Bitts-Jackson

When Donald Trump declared he’d build a “great, great wall” to keep Mexican immigrants out of the United States, he tapped a wellspring of anxieties on both sides of the national immigration-reform debate. But relatively little is understood about the people at the heart of the matter and how and why they are here.

“There’s a kind of assumption about how and why immigrants migrate, and it tends to shape how we understand America as a country, but it is just that—an assumption," says Eric Vazquez, a visiting assistant professor of American studies and expert in Latino/a and transnational American studies. "Given the climate we're in, I think it's worth understanding the specific, different circumstances that bring people to the United States."

Students in Vazquez’s Introduction to Latina/o Studies course can help. Using story-mapping software that connects background information, charts, images and statistics to related sites on a virtual map, they created interactive projects that offer deep context to real-life stories of immigration and migration to the U.S. Two of the projects are available online.

Working in small groups, the students examined the sociopolitical conditions that compel migration from a given country and at a given time. They also delved into U.S. immigration history; the evolving economic systems that bring people from Central America, Mexico, Cuba and Puerto Rico into the U.S.; the commonplace violence many migrants face on that journey; and the diverse ways they become part of American society.

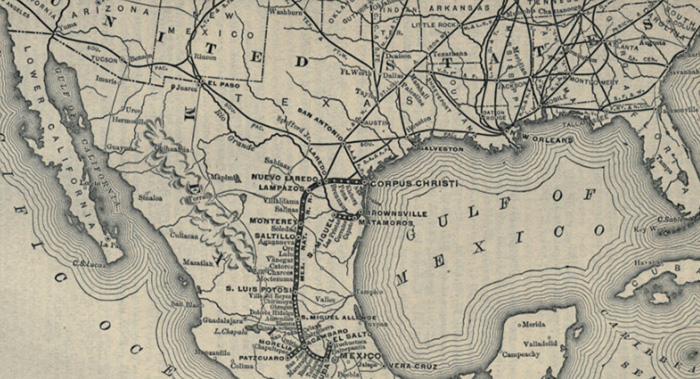

One online student project tells the story of Luis Perez, a runaway and child soldier in the Mexican army who, after honorable discharge at age 13, fled to 1920s America with $20 in his pocket, traveling from Albuquerque to California in pursuit of an American education. The student-researchers flesh out Perez’s story, explaining epidemics in Mexico during his childhood, the dangers of traveling by train from Mexico to the U.S., the naturalization process for Mexican immigrants a century ago and the stipulations of the U.S. Immigration Acts of 1917 and 1924.

The other student project available online is rooted in Oscar Martinez’s The Beast, an unflinching 2013 account of a cross-Mexican train and the Central American immigrants who ride on its roof, in hopes of making better lives in the U.S. As they move readers through train-hoppers’ stories, the students also trace the train’s snaking path on a map, pointing out sites of social, political and economic unrest as well as the many dangers and predators the immigrants encounter along the way.

By examining the historical and current circumstances that lead to immigration—both those in the countries of origin and in the U.S.—we come to understand that longstanding assumptions and national narratives may not ring true across time, Vazquez says. “We just always assume that we're in a progress narrative—that we're heading toward better lives for all Americans. That's not necessarily true,” he adds. “Before we make a judgment of immigration policy, we really need to have a deeper understanding of how it all works."

Learn more

- “The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail”

- “El Coyote/The Rebel”

- Latin American, Latino & Caribbean Studies

- Latest News

Published June 15, 2016