Visualize

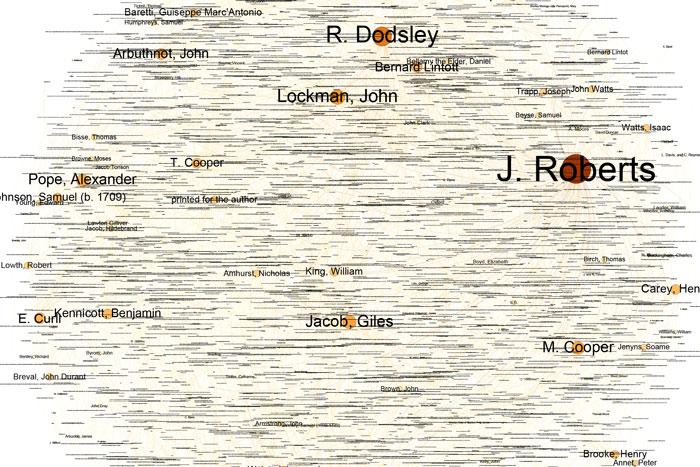

This year’s Digital Boot Camp explored digital curation, and the projects often resulted in data visualizations such as this one, created by Mary Naydan ’15. The image is a visual representation of the frequency of occurrence of various 18th-century poets across 17,422 lines of data.

Students bring data to life though the Digital Boot Camp

by Tony Moore

Projects. They usually have tight parameters, strict requirements and uncrossable boundaries. Dickinson's Digital Boot Camp (DBC) projects are a little different.

“There are no rules as far as what projects students bring in,” says Patrick Belk, the postdoctoral fellow in the digital humanities running this year’s DBC. “I tell them to have a compelling narrative, images, text and be thinking of building a Web site. Beyond that, whatever they come up with, they come up with.”

Mapping and visualizing

Funded by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Dickinson’s DBC was launched last year under the guidance of Chris Francese, Asbury J. Clarke Professor of Classical Studies and Dickinson’s digital-humanities overlord.

“Students are not just learning how to build Web sites; they’re figuring out how to analyze and present knowledge well in a digital format, how to tell meaningful stories with data,” Francese says. “It’s a traditional liberal-arts skill and essential to the purpose of a Dickinson education.”

This year, the DBC found its physical and spiritual home in Dickinson’s Archives & Special Collections and focused less on new-media production and more on digital curation. What this means, essentially, is that students took existing texts, used XML to make them readable by both machines and people and then mined them for data and created visualizations of those data (such as the one in the photo above).

Katy Purington ’15 (classical studies) jumped into the boot camp straight from a fall internship with the classics department and its Dickinson College Commentaries (DCC), through which she analyzed visual interpretations of the Aeneid.

“I signed up for the DBC because I wanted to be able to do more with the DCC project, as well as apply the skills after I graduate this spring,” says Purington, whose DBC project set out to map the Aeneid and discuss the importance of each location. “There are a lot of places in the Aeneid that would have been significant to Romans reading the text, but modern readers often don’t know where these places are.”

The time and space to explore

Harris Risell ’16 (English) says he was initially drawn to the DBC when he learned that many participants each year go on to work with faculty members on digital projects.

“Working with professors is exciting and challenging,” says Risell, whose project involved digitizing English department newsletters from 1967 to 2009 to examine the change in location of the authors, an exercise that has revealed elements such as emerging multicultural and international voices coming into the department. “The idea of having access to an impressive amount of information about Drupal, ArcGIS, XML and Gephi—and being given the time and space to explore with and integrate this information into my own project—was very appealing to me.”

Risell is now applying his new skills to a project for Belk’s Web site, the Pulp Magazines Project, which includes marking up American fiction magazines published from 1896 to 1946, aggregating that data through the Advanced Research Consortium and partnering with ModNets (Modernism on the Net) and the Library of Congress.

Data and the digital humanities

Two other students are also working with their professors on post-DBC projects: Maurice Royce ’16 (computer science) is collaborating with Blake Wilson, professor of music, to build a public database with information about oral poetry from the Italian Renaissance, and Mary Naydan ’15 (English) is working with Jacob Sider Jost, assistant professor of English, on a project that has collected 17,422 lines of entries on 18th-century poets and their books.

“On a base intellectual level, humanities research deals with data,” Belk says, “and at this point, with the digitization of archives, data is becoming so unwieldy, there's so much of it. The idea of the semantic Web is to have everything from the entire human record online and accessible, to help order it and make sense of it.”

For Risell, the DBC brought some order to projects he hasn’t even started yet.

“I’m now more aware of how these skills can clearly and often persuasively provide evidence for an argument or tell a story,” he says. “Looking forward, I see these skills enhancing the projects and presentations I’ll be working on for my courses and giving me an advantage now and in my professional life after Dickinson.”

The DBC was additionally facilitated by Waidner-Spahr Library’s Don Sailer '09, library digital projects manager; Daniel Plekhov ’14 and Michael D'Aprix ’14; and Leah Orr, visiting assistant professor of English.

Learn more

- Read about last year's DBC: "Less Yak, More Hack."

- Digital Humanities at Dickinson

- Department of Computer Science

- Department of Classical Studies

- Department of English

Published February 11, 2015