Independent From the Ground Up

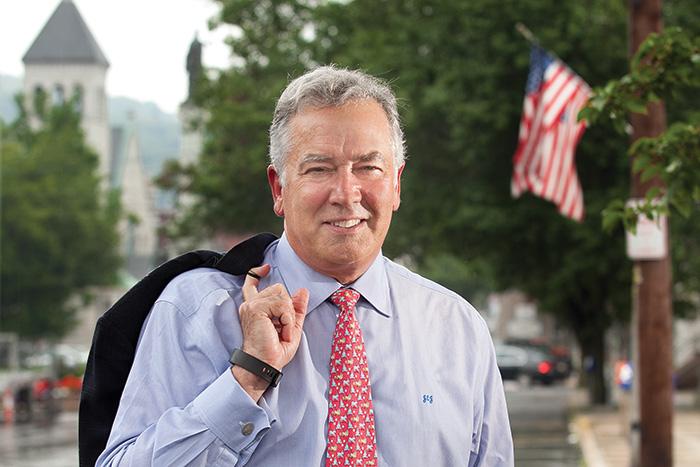

Photo by Carl Socolow '77.

by Michelle Simmons

There’s something about geology and Judge John E. Jones III ’77, P’11.

Jones was born and raised in Schuylkill County, deep in Pennsylvania’s anthracite-coal country. His grandfather William, born in 1895 to Welsh immigrants, was one of the thousands of breaker boys working 10 hours a day, six days a week sifting and sorting slate and other impurities along the conveyor belts and chutes that spit out tons of coal each day. With only an eighth-grade education, William eventually completed correspondence courses in civil engineering and bought stakes in the mines he had worked in as a child.

“He was a totally self-made man, who believed in education,” Jones says.

At the time, no one could imagine the trajectory his family would take, that about a century later William’s grandson would be appointed as a federal judge to the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania.

And no one could further imagine that Jones would decide two cases, nearly 10 years apart, on two of the three issues that arguably form the bedrock of social conservatism in the United States: evolution in 2005 and same-sex marriage this past May.

The first lawyer in his family, Jones majored in political science at Dickinson, earned his J.D. from the Dickinson School of Law and clerked for Guy A. Bowe ’40, president judge of Schuylkill County and an important mentor. He then moved to private practice—still in his home town of Pottsville—while becoming a mover and shaker in Pennsylvania GOP circles. In 1995 he was named to chair the Pennsylvania Liquor Board, where he served for seven years, until his appointment in 2002 by President George W. Bush to the federal bench.

From the beginning of his tenure, Jones showed a propensity for independent thought, along with a clear, concise prose style. A few cases nibbled at the edges of the culture wars, such as Bair v. Shippensburg University, in which he struck down provisions of the university’s speech code; but in 2005, he drew Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District, the first federal legal challenge to the teaching of intelligent design. The trial triggered massive, 24/7 media coverage.

In a widely lauded—and reviled—139-page decision, Jones took the Dover School Board members to task not only for their “breathtaking inanity” in pursuing a creationist agenda in the classroom but also for outright lying during earlier depositions. “The students, parents, and teachers of the Dover Area School District deserved better than to be dragged into this legal maelstrom, with its resulting utter waste of monetary and personal resources,” he wrote.

This focus on the personal, individual consequences of the cases over which he presides would become a hallmark for Jones. “I tell my clerks, every one of them, when they come on board, these are not just files,” he says. “These are not screenshots on a computer. These are people. And trite though that may be, 22 years of practicing law taught me that every case has a face.”

Jones himself was catapulted into a maelstrom of another sort. “We got bags of mail—I mean, bags,” he recalls. “We were pouring them out on the table, and that went on for days.” Some of the mail contained threats against him and his family serious enough to warrant round-the-clock U.S. Marshal protection, and he became a favorite punching bag for conservative commentators, who wasted no time in condemning him for his “judicial activism.”

“What was repeatedly misapprehended about the Dover case was that it had to do with the origin of man,” Jones explains in Blindfolds Off: Judges on How They Decide. “What was on trial—the somewhat seminal question in the case—was this concept known as intelligent design. ... It dovetailed extensively with creationism and was really the successor to the concept of creation science, which had been rejected in prior court decisions.”

Dover endowed Jones with a celebrity status rare among the judiciary. In 2006 he was named by Time magazine to its 100 Most Influential People in the World list. In a New Yorker article about the case, the writer described him as having “the rugged charm of a 1940s movie star; he sounded and looked like a cross between Robert Mitchum and William Holden.” There was speculation that Tom Hanks would play Jones in a film about the trial.

“The experience had some surreal aspects to it,” he deadpans.

Jones has used that status to his advantage and has become a different sort of activist—one for the concept and practice of “judicial independence”—and he speaks as much as his heavy schedule allows in its defense (including an upcoming Dec. 2 visit to Dickinson for a panel discussion hosted by the Clarke Forum for Contemporary Issues).

“We don’t rule to please the person who appointed us,” he says. “We rule according to the Constitution and the Bill of Rights and the law that we are applying in any particular case. A lot of people say, ‘Who is this one judge to decide this case?’ Well, federal judges are appointed by the U.S. president and confirmed by the U.S. Senate. So, in the popular sense we may be unelected officials, but we don’t just fall out of the sky and onto the bench. We are a product of the process, and we are a member of a co-equal branch of government.”

This summer, Jones had another opportunity to educate the public about the importance of judiciary independence, when he drew the high-profile case Whitewood v. Wolf, in which he struck down Pennsylvania’s ban on same-sex marriage. His decision, appearing among a rapid succession of similar verdicts in other states, heralded a shifting-of-the-ground-beneath-your-feet kind of change in the culture wars.

This time, in a much briefer opinion (only 39 pages), Jones laid out the long history of systemic discrimination against LGBT individuals, such as the criminalization of homosexuality, the bans against hiring LGBT individuals or denying them housing and the prevalence of hate crimes. The case did not go to trial, as both sides agreed on the facts: “The lawyers concluded that the harms were evident,” says Jones, “even though they disagreed on the legal result.” In essence, the defendant (the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania) was arguing that government-sanctioned discrimination was perfectly constitutional.

Jones drew from another civil-rights battle to undergird his decision. “In the 60 years since Brown [v. Board of Education] was decided, ‘separate’ has thankfully faded into history, and only ‘equal’ remains,” he wrote. “Similarly, in future generations the label same-sex marriage will be abandoned, to be replaced simply by marriage. We are a better people than what these laws represent, and it is time to discard them into the ash heap of history.”

In the following days, he again was both hailed and pilloried in the national media (with social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook amplifying every comment), and his staff got the requisite cranky calls, but he notes that this case didn’t get the same “visceral reaction” as Dover had. “Maybe on this issue the public is a little more enlightened,” he muses.

Meanwhile, Jones continues to manage his mountainous case load (“several hundred civil cases that are active and probably about 100 criminal cases on the docket”) and teaches a course in criminal law at the Pennsylvania State University Dickinson School of Law. He still commutes every day between his Pottsville home (often stopping first at a local donut shop for his morning coffee) and Harrisburg, where his chambers are located.

And while many of his neighbors might disagree with his views—some of them vehemently—he’s still a hometown favorite. “People are so wonderful and respectful,” he says, “not because I’m so great, but because I’m their guy. My wife always says, ‘They can argue about stuff, but if John did it, it’s OK.’ ”

His chambers, which overlook the State Capitol Building, feature an assortment of awards and honors he’s received over the years, including the Geological Society of America’s President’s Medal, which sits next to an award commemorating his service to a local fire company. Nearby hangs a pair of boxing gloves signed by Muhammad Ali (a gift from legendary trainer Angelo Dundee), and on his desk rests a gavel, carved from anthracite.

“We are called, as federal judges, the last great generalists,” Jones says. “On any given day, my docket can involve myriad differences, scientific points, engineering. So the tools you get and the intellectual curiosity that’s developed as a liberal-arts student—all of that comes to bear when you have to pivot from one case to another. Nothing prepared me better than the liberal-arts education I received at Dickinson. Obviously, you need the legal education, but the intellectual curiosity is a parallel tool in what I do, day after day.”

In 2009, when Jones received the Geological Society medal on the bicentennial of Charles Darwin’s birth, among the 1,000-plus audience members was Noel Potter, professor emeritus of geology. “When I sat in Noel Potter’s geology class some 36 years ago, neither Professor Potter nor I could have imagined this day would come,” Jones told the assembly of scientists. “And for those of you who think there’s some guy sitting in the last row of your classroom and he’s not paying attention. ... I’m here to tell you that maybe he was paying attention, and maybe he was actually learning something.”

Read more from the fall 2014 issue of Dickinson Magazine.

Learn More

Published November 5, 2014